The Paradox Amid Consensus: From Risk Warnings to the Norm of Competition

Risk dominates current discussions on artificial intelligence governance. This July, Geoffrey Hinton, a dual laureate of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine and the Turing Award, delivered a speech at the World Artificial Intelligence Conference in Shanghai. The title remained the one he has repeatedly used since leaving Google in 2023: “Will Digital Intelligence Replace Biological Intelligence?” He emphasized once again that artificial intelligence may soon surpass humanity and threaten our survival.

Scientists and policymakers from China, the United States, European countries, and beyond nodded in grave agreement. However, beneath this superficial consensus lies a profound paradox in AI governance: at conference after conference, the world’s brightest minds identify shared risks, call for cooperation, and sign declarations. Yet the moment the meetings end, the world reverts to a state of fierce competition.

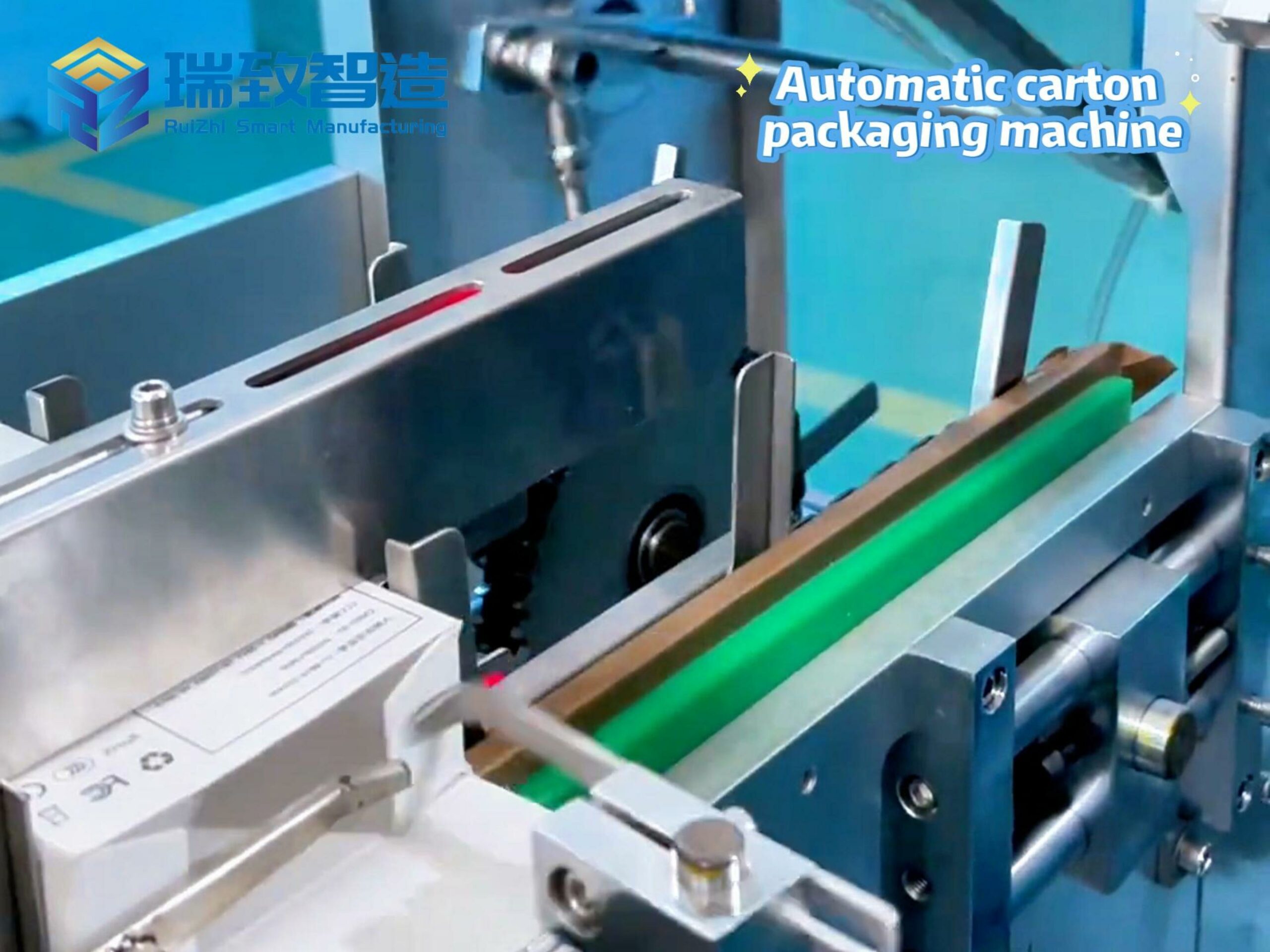

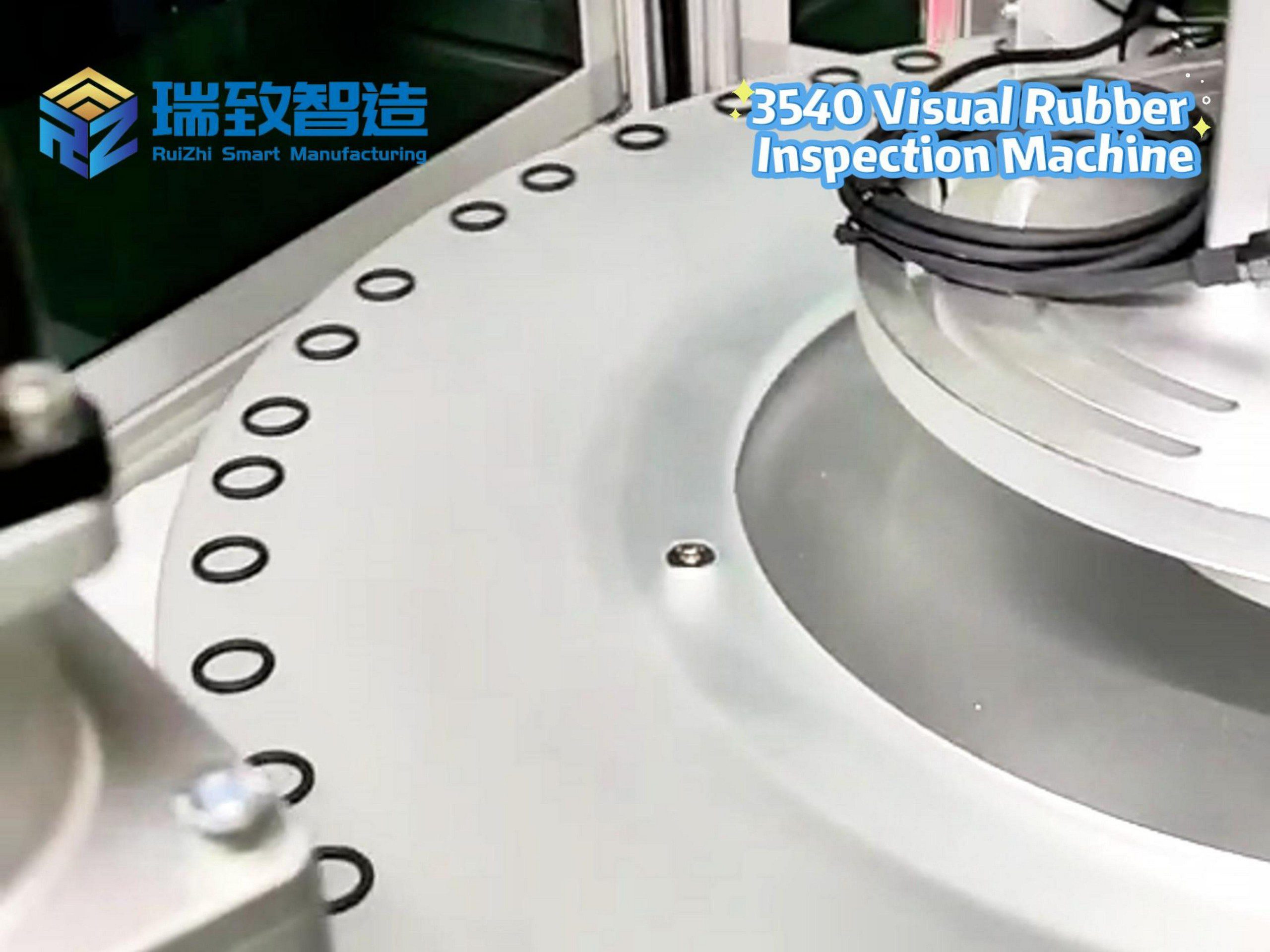

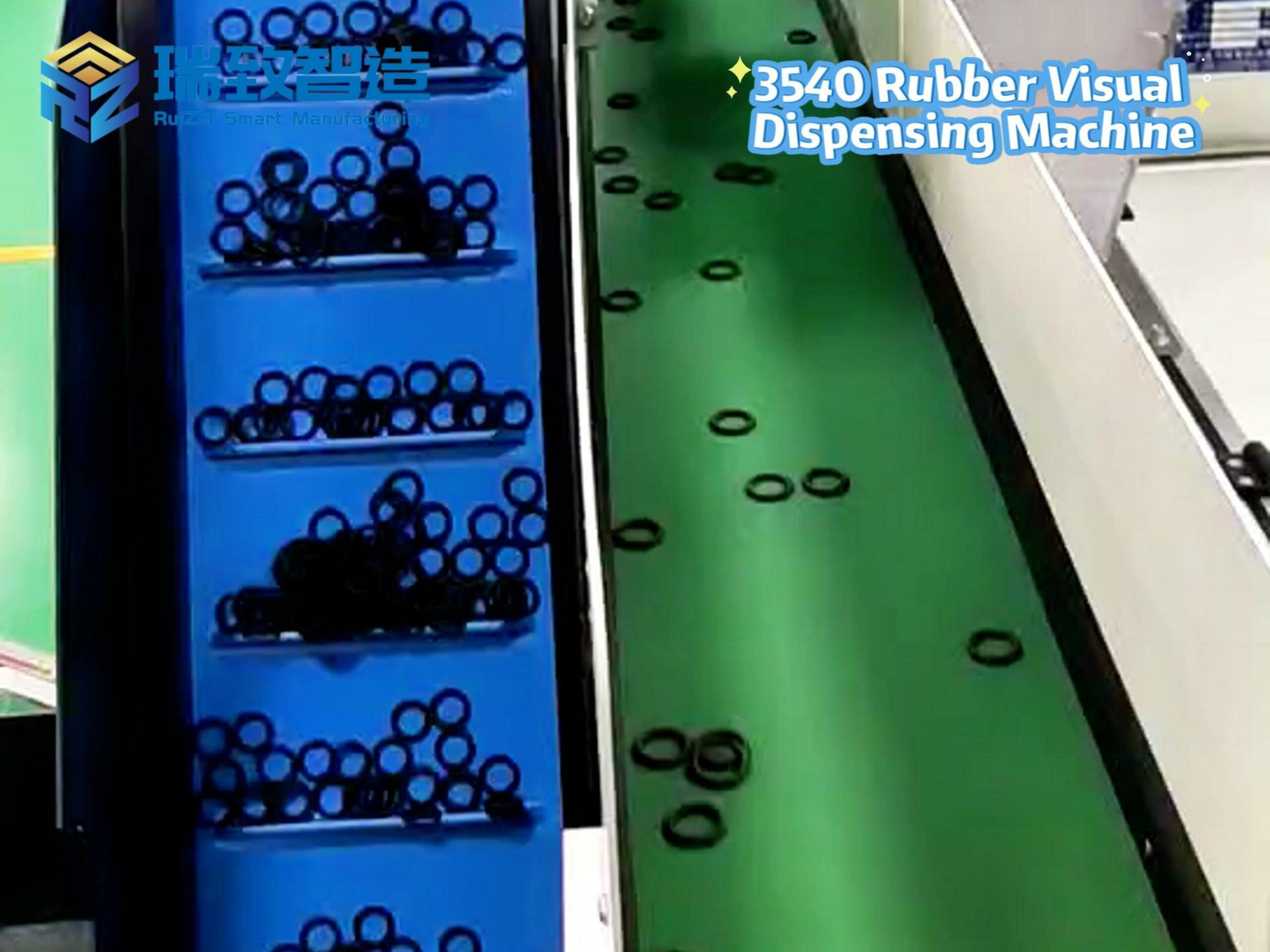

This paradox has troubled me for years. I trust in science, but if the threat truly survival, why can’t even the instinct for self-preservation unite humanity? Only recently did I realize a disturbing possibility: these risk warnings fail to foster international cooperation because defining AI risks has itself become a new arena for global competition. Even in niche domains like manufacturing automation—such as the precision calibration of Обладнання для автоматичного розташування пружинних лотків, where AI-driven vision systems and robotic arms dictate production standards—disagreements over “acceptable error margins” or “safety thresholds” subtly reflect broader battles over technical dominance and market access.

The “Construction” of Risks: From Scientific Assessment to Strategic Gamesmanship

Traditional technology governance follows a clear causal chain: first identify specific risks, then develop governance solutions. The dangers of nuclear weapons are straightforward and objective—blast yield, radiation range, radioactive fallout. Climate change has measurable indicators and an increasingly solid scientific consensus. But artificial intelligence is entirely different; it is like a blank canvas. No one can fully convince everyone whether the greatest risk is mass unemployment, algorithmic discrimination, the takeover by superintelligence, or some entirely new threat we have yet to imagine.

This uncertainty has transformed AI risk assessment from a scientific inquiry into a strategic game. The United States emphasizes “existential risks” posed by “frontier models”—terminology that focuses attention on Silicon Valley’s advanced systems, framing American tech giants both as sources of risk and as essential partners in risk control. Europe focuses on “ethics” and “trustworthy AI,” extending its regulatory expertise from data protection to artificial intelligence. China advocates that “AI safety is a global public good,” arguing that risk governance should not be monopolized by a few nations but should serve humanity’s common interests—a narrative that challenges Western dominance while calling for a multipolar governance structure.

Corporations are equally adept at shaping risk narratives. OpenAI emphasizes “alignment with human goals,” highlighting both genuine technical challenges and its own research strengths. Anthropic promotes “constitutional AI,” precisely targeting domains where it claims expertise. Other companies skillfully select safety benchmarks that favor their technical approaches, implying that risks lie solely with competitors who fail to meet these standards. Computer scientists, philosophers, economists—each professional community shapes its own value through narratives, whether warning of technical catastrophes, exposing moral hazards, or predicting labor market upheavals.

As a result, the causal chain of AI safety has been completely inverted: we first construct risk narratives, then deduce technical threats; we first design governance frameworks, then define the problems that require governance. The process of defining problems itself creates causality. This is not a failure of epistemology but a new form of power—making one’s definition of risk the unquestioned “scientific consensus.” How we define “artificial general intelligence,” which applications constitute “unacceptable risk,” and what qualifies as “responsible AI”—these answers will directly shape future technological trajectories, industrial competitive advantages, international market structures, and even the world order.

Seeking Coordination Amid Plurality: Redefining the Possibilities of AI Governance

Does this mean that AI safety cooperation is destined to be empty talk? On the contrary, understanding the rules of the game allows for more effective participation.

AI risks are constructed. For policymakers, this means advancing their own agendas in international negotiations while understanding the genuine concerns and legitimate interests behind others’ positions. Acknowledging constructiveness does not mean denying reality—regardless of how risks are defined, solid technical research, robust contingency mechanisms, and practical safeguards remain essential. For enterprises, this means considering diverse stakeholders when formulating technical standards and abandoning a “winner-takes-all” mindset; true competitive advantage stems from unique strengths rooted in local innovation ecosystems, not opportunistic positioning. For the public, this requires cultivating “risk immunity”—learning to discern the interest structures and power relations behind different AI risk narratives, neither paralyzed by doomsday prophecies nor seduced by technological utopias.

International cooperation remains indispensable, but we must rethink its nature and possibilities. Instead of pursuing a unified AI risk governance framework that is neither achievable nor necessary, we should acknowledge and manage the plurality of risk perceptions. The international community does not need a single overarching global agreement but rather “competitive governance laboratories” where different governance models prove their value in practice. This polycentric governance may appear loose, but it can achieve higher-level coordination through mutual learning and checks and balances.

We habitually view AI as just another technology requiring governance, without realizing that it is reshaping the very meaning of “governance.” The competition to define AI risks is not a failure of global governance but its inevitable evolution—a collective learning process as humanity confronts the uncertainties of trans formative technology.